“It requires much more imagination

to grasp the obvious than the

recondite.”— William Barrett

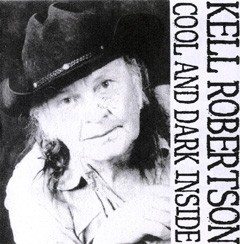

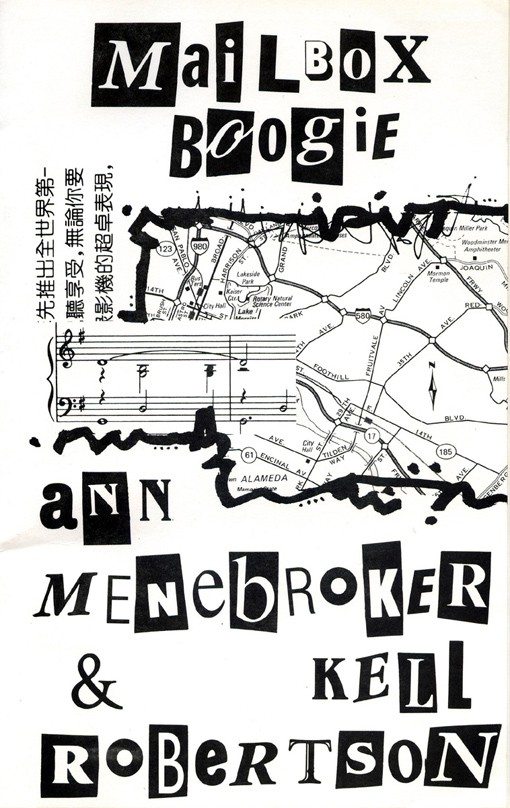

Sometime last year, while driving back home from Santa Fe around midnight, I tuned in to KSFR-FM, an NPR station , and heard Kell Robertson playing and singing from his new CD (2010), Cause I’m Crazy, which I have, know and liked a lot. He writes the songs (poems), arranges them, plays and sings them. He’s been doing this for years, in concerts, clubs, bars and festivals, and he’s gotten good reviews from the Santa Fe New Mexican to Rolling Stone, where Grover Lewis said: “Kell Robertson is a national treasure, and they don’t make them anymore.”

Robertson doesn’t make a big distinction between songs and poems, often includes poems in his books that later appear on his CDs as songs and that is, perhaps, as it should be, because Robertson is a folk poet/singer or, perhaps closer to his style, a country/western singer-songwriter. What he is not is a “cowboy poet.” Lawrence Ferlinghetti once referred to him by that term and, although Robertson likes Ferlinghetti he absolutely denies he is a “cowboy poet.” And he’s right! He worked on a ranch, he likes to ride horses but was never a cowboy. Here’s the direct quote: “I would say that Kell Robertson is one fine cowboy poet, worth a dozen New Yorker poetasters. Let them listen and hear a voice of the real American out there.” If you hear his CDs and read his books, you will know that, except for the cowboy part, the rest is true.

Robertson doesn’t make a big distinction between songs and poems, often includes poems in his books that later appear on his CDs as songs and that is, perhaps, as it should be, because Robertson is a folk poet/singer or, perhaps closer to his style, a country/western singer-songwriter. What he is not is a “cowboy poet.” Lawrence Ferlinghetti once referred to him by that term and, although Robertson likes Ferlinghetti he absolutely denies he is a “cowboy poet.” And he’s right! He worked on a ranch, he likes to ride horses but was never a cowboy. Here’s the direct quote: “I would say that Kell Robertson is one fine cowboy poet, worth a dozen New Yorker poetasters. Let them listen and hear a voice of the real American out there.” If you hear his CDs and read his books, you will know that, except for the cowboy part, the rest is true.

And the surprising thing is that many New Mexicans, including a lot of poets, have never heard of Robertson and don’t know his poetry though he’s lived in the Santa Fe area for years. (Perhaps a legend to some, a will-o-the -wisp to others). Partly that’s because he has “flown under the radar,” keeping things “low key” and also because his books, generally issued by small poetry presses in small editions, are often out of print and hard to get. Yet many local poets, as well as many nationwide (like Ferlinghetti), consider Robertson to be one of the best poets in the state, some say the best. That may depend partly on how you relate to the experiences he recounts, which reflect his life, which has not been a life of wealth and ease but rather the opposite, a hardscrabble life, with little formal education, working menial jobs, traveling around by jumping trains, long Greyhound trips, or hitchhiking. His poems often speak of his experiences in specific places from New York City to San Francisco (where he lived for an extended time, participating in the poetry scene there with many well known poets), from Yuma to Tulsa, El Paso, Albuquerque, Juarez, Oregon, Santa Fe, Bernalillo (see his poems “Parade” and “Coronado National Monument”), and even to Placitas, where he once worked at the famous Thunderbird Bar (burned down years ago) which had many a poetry reading with well known poets.

If there is one category Robertson will accept to describe himself, it is “outlaw poet” for he has been the Outsider all his life. He’s been thrown in jail in Texas, thrown out of bars, drank wine (and whatever) with hobos under bridges, seen Skid Row up close, wandered drunk around the desert till collapse, and had every kind of pick-up job you can name, including working as a laborer, card dealer, dishwasher, movie theater usher, DJ, fruit picker, farm worker, bartender and “carnie.” Also, he says: “magician, coyote.” It’s all in his poetry. Survival was the goal early on in life after his father abandoned Kell (age two) and his mother, then his stepfather (an alcoholic) threw him out at age 13. As he says in his poem “Auto-Bio”: “It was my mother/who gave me words./My father ran away/but left me music./My stepfather/gave me fear/and guns./My brother and sister/were born dead.” More details emerge from an excellent interview Robertson had with R.D. Armstrong (Lummox Journal, July, 2000): “It was my mother who turned me on to reading. (…) Mama had two sets of books in the house. The Collected Works of Zane Grey and Collected Works of William Shakespeare. That, and a dictionary was my early education. ” (He was able to finish 8th grade, doesn’t remember more than three months at any one school, as his family traveled around). Robertson says his stepfather “hated the fact that I read books and loved school. (…) I was a freak. I loved books. I loved the very process of learning.” When he was thrown out he says: “…my stepdad…figured it was time I get away from all that book learning, get a job and be on my own.” This was in Louisiana, where his mother took him to one concert that would change his life. Hank Williams performed. Says Robertson: “Hank was drunk and he knocked over the microphone but when he actually started to sing, he just reached out and laid all that loneliness on everybody. I decided right then, I wanted to do something like that.”

If there is one category Robertson will accept to describe himself, it is “outlaw poet” for he has been the Outsider all his life. He’s been thrown in jail in Texas, thrown out of bars, drank wine (and whatever) with hobos under bridges, seen Skid Row up close, wandered drunk around the desert till collapse, and had every kind of pick-up job you can name, including working as a laborer, card dealer, dishwasher, movie theater usher, DJ, fruit picker, farm worker, bartender and “carnie.” Also, he says: “magician, coyote.” It’s all in his poetry. Survival was the goal early on in life after his father abandoned Kell (age two) and his mother, then his stepfather (an alcoholic) threw him out at age 13. As he says in his poem “Auto-Bio”: “It was my mother/who gave me words./My father ran away/but left me music./My stepfather/gave me fear/and guns./My brother and sister/were born dead.” More details emerge from an excellent interview Robertson had with R.D. Armstrong (Lummox Journal, July, 2000): “It was my mother who turned me on to reading. (…) Mama had two sets of books in the house. The Collected Works of Zane Grey and Collected Works of William Shakespeare. That, and a dictionary was my early education. ” (He was able to finish 8th grade, doesn’t remember more than three months at any one school, as his family traveled around). Robertson says his stepfather “hated the fact that I read books and loved school. (…) I was a freak. I loved books. I loved the very process of learning.” When he was thrown out he says: “…my stepdad…figured it was time I get away from all that book learning, get a job and be on my own.” This was in Louisiana, where his mother took him to one concert that would change his life. Hank Williams performed. Says Robertson: “Hank was drunk and he knocked over the microphone but when he actually started to sing, he just reached out and laid all that loneliness on everybody. I decided right then, I wanted to do something like that.”

The late poet Todd Moore, in his illuminating essay “Pure Blood Primal: The Poetry of Kell Robertson” (Outlaw Poetry Network on metropolisfrance.com), says : “Kell Robertson has somehow become the prototypical outlaw of Outlaw Poetry….what he brings…is a primal and passionate sense of all the old stories told around freight cars and old trucks and bonfires and barn stalls. This is something that can’t be taught in writing schools because the old storytellers are almost all gone. The old talking is also nearly gone and you can’t fake it back, you can’t dance it back, you can’t dream it back. The wind has blown a lot of that old talk away.” But Kell is still here, still talking, still writing, still performing.

So who are Robertson’s favorite poets/songwriters/performers, other than Hank Williams? Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Rosalie Sorrels, Van Morrison and especially his friend, the late Utah Phillips (1935-2008), with whom he shared a dedication to (among other things) the Wobblies (the Industrial Workers of the World, who were persecuted constantly in the U.S. as they tried to organize workers to fend for their rights). Like Phillips, Robertson seems to be a born storyteller. When Phillips died, there were two tribute events for him in New Mexico, one in Albuquerque (Peace & Justice Center) and another in Santa Fe (Santa Fe Brewing Co.). Kell Robertson performed at the latter, along with other poets and musicians.

So who are Robertson’s favorite poets/songwriters/performers, other than Hank Williams? Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Rosalie Sorrels, Van Morrison and especially his friend, the late Utah Phillips (1935-2008), with whom he shared a dedication to (among other things) the Wobblies (the Industrial Workers of the World, who were persecuted constantly in the U.S. as they tried to organize workers to fend for their rights). Like Phillips, Robertson seems to be a born storyteller. When Phillips died, there were two tribute events for him in New Mexico, one in Albuquerque (Peace & Justice Center) and another in Santa Fe (Santa Fe Brewing Co.). Kell Robertson performed at the latter, along with other poets and musicians.

Robertson, from a family of small farmers, was born in a tiny, southeast Kansas village near Elk City. As the Todd Moore wrote in his essay: “Kell was born in 1930, he is a product of the Great Depression. His was a hard-scrabble childhood. Born in Dustbowl Kansas, raised by a stepfather who shot pop bottles off his head for the hell of it.” When he was out on his own at a young age, Robertson had to become a shape-shifter to survive, like the protagonist of a picaresque novel, going from one adventure to another, escaping from one crisis or situation to the next, re-inventing himself according to the necessities of different realities. Like a magician of himself, he appeared, disappeared and re-appeared all across the country like the sudden coyote who crosses the road, between cars, or disappears in the rear-view mirror.

The coyote figure, image, role, is mentioned in quite a few of Robertson’s poems and in discussions with him he says it’s one of his favorite animals. He especially likes the figure of the coyote as Trickster in Native American mythology, perhaps because he has had to live by his wits from an early age: The coyote is a survivor. And the coyote is also like a magician in his cleverness. But there is also another reason: At one time, he had friends in the Native American Church and partook of peyote with them. As a part of this activity, he was given a “spirit/totem animal”–the coyote. In his poem “Peyote Morning,” he ends it humorously with: “An ant hurries across the concrete/struggling with a piece of peyote./What is he going to do with that?“

The coyote figure, image, role, is mentioned in quite a few of Robertson’s poems and in discussions with him he says it’s one of his favorite animals. He especially likes the figure of the coyote as Trickster in Native American mythology, perhaps because he has had to live by his wits from an early age: The coyote is a survivor. And the coyote is also like a magician in his cleverness. But there is also another reason: At one time, he had friends in the Native American Church and partook of peyote with them. As a part of this activity, he was given a “spirit/totem animal”–the coyote. In his poem “Peyote Morning,” he ends it humorously with: “An ant hurries across the concrete/struggling with a piece of peyote./What is he going to do with that?“

In the R.D. Armstrong interview, Robertson says: “What Gino Sky (Clays) called ‘the wild dogs of poetry’. I guess I’m one of those.” This fits in with the coyote image (which is similar to the fox in European culture). A commentarist named Larry Ellis has said of the Native American Coyote Trickster figure: “the trickster…is at once the scorned Outsider and the Culture Hero, the Mythic Transformer and the buffoon, a creature of low purpose and questionable habits…he has the skill of a shape-shifter…creates through destruction and succeeds through failure…he is associated with the landscape he travels…personifies marginality…straddling the juncture of two worlds, he belongs to neither and both. He is the creature of this reality and its shaman.” This all seems to fit the role of Robertson as poet, performer, Outsider, phoenix.

Todd Moore wrote about one particular poem of Robertson’s, “The Passionate Coyote” (in this issue): “…after a while I realized that this poem is a kind of abbreviated Kell Robertson bio. (…) now, every time I see No Country for Old Men, which was filmed in one or two of Albuquerque’s old hotels, I think of this poem and am reminded of the fate of the poet in America. The dead coyote (in the poem) is all that’s left of the poet. His eyes have all morphed back into poems.” .

So is Robertson a “Culture Hero” who has stood up for what he believes in, an anti-hero who has survived in spite of many close scrapes, the protagonist of his own tragedy, comedy or tragi-comedy, a folk hero vs. an elite hero, in the dramas of his journeys like a wandering troubadour, a constant defender of the underdog and critic of the abuses the Power Elite visits on the people? Probably all of the above! But as he says in his poem “Song” (from his book The Goofy Goddess on the Wall): “They tell me to act/my age/as if it were a role that I could play/before the drama critics of/ this life of mine.” But he’s not an actor in his own movie, he’s the Poet who makes himself vulnerable by telling his story, but that is also his power. One of the things that keeps many from being good poets is they are afraid to reveal these truths of their lives. (Actually, Robertson was also a film actor at least once, a bit part in Sam Peckinpah’s famous classic “The Wild Bunch,” in which he has one short line and is the first horseman killed.)

So is Robertson a “Culture Hero” who has stood up for what he believes in, an anti-hero who has survived in spite of many close scrapes, the protagonist of his own tragedy, comedy or tragi-comedy, a folk hero vs. an elite hero, in the dramas of his journeys like a wandering troubadour, a constant defender of the underdog and critic of the abuses the Power Elite visits on the people? Probably all of the above! But as he says in his poem “Song” (from his book The Goofy Goddess on the Wall): “They tell me to act/my age/as if it were a role that I could play/before the drama critics of/ this life of mine.” But he’s not an actor in his own movie, he’s the Poet who makes himself vulnerable by telling his story, but that is also his power. One of the things that keeps many from being good poets is they are afraid to reveal these truths of their lives. (Actually, Robertson was also a film actor at least once, a bit part in Sam Peckinpah’s famous classic “The Wild Bunch,” in which he has one short line and is the first horseman killed.)

Kell Robertson was also a U.S. Army soldier sent to serve in the Korean War in the 1950s, a conflict that was not a positive experience: “I got out of the military because I hated it, hated war, hated the whole thing.” This and poetry are two bonds that he had with the late, New Mexico poet Keith Wilson of Las Cruces, who also served in the Korean war, and came out of it with the same anti-war views. Wilson’s book of poems, Graves Registry, nominated for a National Book Award for Poetry, describes the author’s experiences in Korea. Wilson is greatly admired by many but especially by Robertson, for the excellence of his poetry, his style, his way of structuring the poem, as well as the quality of the man.

Other poets whose work Robertson likes include Carl Sandburg, Robert Frost and a now relatively unknown poet from Colorado, Thomas Hornsby Ferril (1896-1988), known for poems of the western landscape. Ferril worked as a journalist in Denver and published six books of poetry including High Passage (Yale Younger Poets Award, 1926); Westering; and Anvil of Roses. Robertson believes Ferril is a poet who needs to be known and recognized for his work today.

Robertson’s poetry presents a view of society from the bottom up, through the lens of a poet who knows that reality intimately, as is obvious in his songs and poems, from “Migrant farm worker” to “Junkie Eyes” (from his latest CD). One of his major poems is also the name of his most well known book A Horse Called Desperation, which starts off with a quote from Proverbs 12:10: “A righteous man regardeth the life of his beast.” Robertson is a good rider, a horseman who loves horses, even this one:

I ride a horse called desperation

a bony nag, half blind and mangy

fast only because he has to be

he runs in startled leaps

and cannot see where he is going.

( …….. )

death, as a shrouded figure comes

from our imaginings and the real

death is no more than a twig

snapped in the wind.

This is no regular horse but one which functions on more than one level of meaning: “this horse/…/called desperation/sags/against the wall/out of breath/but ready/for a burst of speed/over the edge of the abyss.” The poet here rides his desperation which dies and resurrects, is seemingly weak but always has enough strength to carry on. We know all humans can be animated by their own desperation and those on the bottom of society are often more desperate. Says the poet: “this horse/potbellied because/he is undernourished/ and overfed, couldn’t leap/over the trimmed hedges/…/but will break them down/for the hell of it/on a windy night/when winds howl/and a full moon/drive his rider mad/this horse of mine/and magic, his eyes/are crazy and dies/rots and rises again/to fall and this time/when he rises/it’s like the sudden interest/of a man on the verge of suicide/…”.

The horse involves magic and clairvoyancy, in western symbolism. This horse may be transportation, but so is desperation, which moves so many in daily life. As Thoreau said: “Most people lead lives of quiet desperation, and go to the grave with a song still in them.” Says the poet: “this horse/my horse/called desperation/is the only horse/that will take me/where I want to go.” Robertson, however, is not quiet, he has been singing his songs.

The horse involves magic and clairvoyancy, in western symbolism. This horse may be transportation, but so is desperation, which moves so many in daily life. As Thoreau said: “Most people lead lives of quiet desperation, and go to the grave with a song still in them.” Says the poet: “this horse/my horse/called desperation/is the only horse/that will take me/where I want to go.” Robertson, however, is not quiet, he has been singing his songs.

And finally, he says:

The coffee is cold

the fire has gone out

the girl I love sleeps in the arms of my accusers

christ rolled the stone away and went to glory

nobody will serve me anything

in my arrogant despair I turn

to sing my song to a horse

who is too weary to listen

but never too weary to carry me

jerking and screaming through

the stark cold night and the flames.

The poet isn’t “christ,” and his only option is to sing to Desperation. And ride it too! This personified abstraction (Desperation) is real and unreal, tangible and metaphorical that takes the form of a horse. And, as he says in his poem “Cowboy Song,”: “It is 5,000 miles/ from the back of this horse/ to where you sit drinking beer.”

How appropriate that Robertson, many decades ago now, used to put together a little mimeoed poetry publication called Desperado, in which he included many now- well- known poets.

Robertson doesn’t have a webpage, a cell phone, a car, a bank account, a credit card, and little money. He writes every day and types his poems on an old portable typewriter. Over the years a lot of those poems from his typewriter have appeared not only in books but in a lot of poetry publications. In Armstrong’s interview with Robertson, he asks him what his reaction is to not being included in the famous anthology, Outlaw Bible of American Poetry. Robertson indicated he was not happy about it, then says: “I know a barmaid in Texas who has memorized most of my poems. That’ll do.”

Robertson doesn’t have a webpage, a cell phone, a car, a bank account, a credit card, and little money. He writes every day and types his poems on an old portable typewriter. Over the years a lot of those poems from his typewriter have appeared not only in books but in a lot of poetry publications. In Armstrong’s interview with Robertson, he asks him what his reaction is to not being included in the famous anthology, Outlaw Bible of American Poetry. Robertson indicated he was not happy about it, then says: “I know a barmaid in Texas who has memorized most of my poems. That’ll do.”

As for the future state of poetry and creativity in this country, when asked by Armstrong, Robertson says: “Without creativity we’re all dead. (…) Society has always fought the creative impulse. Creativity is always dangerous. Always will be. But without it we’d be truly dead in our hearts and souls. We’d live in a dead place with other zombies. Which is what most of society here in America seems to want to do. (…) Of course, the creative spirit is going to go mad in such a world. (…) But somehow the creative spirits always stumble through.” And he cites an old friend, poet Jack Micheline, who said: “It’s the dead, it’s the dead, it’s the goddamn dead that rule this world!”

Kell Robertson has perhaps been a loner but even with all his traveling, writing and extensive reading , he wouldn’t change a thing, he says. In his poem “Return” Kell explains: “I look for peace/but lack the peace/ to keep it.” As to his life, sometimes on difficult roads, he quotes his mother: “A ship is safe in a harbor, but that’s not what ships are made for.” — Gary L. Brower

FEATURED IN THIS ISSUE: Kell Robertson, Joe Speer, Patricia Clark Smith. Mini – Anthology of Haitian Poets. Jack Hirschman and Boadiba, editors / translators. Mini – Features: Lauren Camp, Catherine Ferguson, Damien Flores, Michael C. Ford, Howard McCord. ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: H. Marie Aragon, Hakim Bellamy, Gary L. Brower, Deborah Coy, John Crawford, Peggy Dobreer, Doris Fields, Jim Fish, Renny Golden, Edward Gonzales, Pamela Adams Hirst, John Knoll, John Macker, E.A.’Tony” Mares, Kendall McCook, Elizabeth Keough McDonald, Don McIver, Couca Mesidor, Carol Moscrip, Sara Marie Ortiz, David S. Pointer, Margaret Randall, Alfonso Reyes, Georgia Santa Maria, Susan Schmidt, Tim Staley, Carine Topal, Rachelle Woods, Martha Yoak.

FEATURED IN THIS ISSUE: Kell Robertson, Joe Speer, Patricia Clark Smith. Mini – Anthology of Haitian Poets. Jack Hirschman and Boadiba, editors / translators. Mini – Features: Lauren Camp, Catherine Ferguson, Damien Flores, Michael C. Ford, Howard McCord. ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: H. Marie Aragon, Hakim Bellamy, Gary L. Brower, Deborah Coy, John Crawford, Peggy Dobreer, Doris Fields, Jim Fish, Renny Golden, Edward Gonzales, Pamela Adams Hirst, John Knoll, John Macker, E.A.’Tony” Mares, Kendall McCook, Elizabeth Keough McDonald, Don McIver, Couca Mesidor, Carol Moscrip, Sara Marie Ortiz, David S. Pointer, Margaret Randall, Alfonso Reyes, Georgia Santa Maria, Susan Schmidt, Tim Staley, Carine Topal, Rachelle Woods, Martha Yoak.

Editor’s Note: MR#4

It never occurred to me that when I published the memorial segment for the late poet Todd Moore in MR#2, that one of the poets who wrote a tribute poem (“Death of a Word Slinger”) for Todd, Joe Speer, would be gone quickly from pancreatic cancer, and that in this issue we would have a memorial segment for him. But that is the case. It has been a sad occasion for me to publish these memorial features, but necessary to let the poets of the state know who is no longer with us.

This is also the case with Patricia Clark Smith (or Pat Smith, as most knew her), and a memorial segment for her is in this issue. I first met Pat in 1970 when I moved to the Albuquerque area to teach at UNM. I lament her demise too, of course, as do many, for she had numerous former students at UNM whom she men-tored (and who became excellent writers), and many friends.

I wish to thank John Crawford for his help in gathering the materials for Pat’s memorial pages, and Pamela Adams Hirst for the same in creating the memorial for Joe. I want readers to know that Joe’s last publication, a book titled Backpack Trekker: A 60s Flashback (Beatlick Press, 2011) was issued posthumously, and is available on Amazon.com. He was able to see the final proof, and even helped proofread some of it, before his untimely death.

Thanks are also appropriate for E.A.’Tony” Mares, MR Advisory Board member, for his introduction to Patrocifio Barela’s work, necessary to guide those unfamiliar with that artist’s sculpture.

Likewise, I am especially pleased to thank Edward Gonzales, (as well as his wife Susanna, who was extremely helpful), renowned New Mexico visual artist and author, for his wonderful paintings we have reproduced on the front and back covers. We are honored to present to our readers these art works, and especially since the front cover presents the talented Taos wood sculptor, Patrocifio Barela. This New Mexican was ignored after his initial appearance on the art scene in New York years ago, but his work is now much appreciated. It is especially pleasing to present two excellent artists at the same time, one through the other.

I am most grateful to Jack Hirschman, guest editor of the Haitian mini-anthology, as well as Boadiba, for collecting and translating Haitian poetry and for their Open Gate anthology (2001, now out of print, but still available online), from which we are using a number of poems.

Also thanks to Kell Robertson for his time and permission to publish so many of his poems, and to his friend Naomi Nordstrom who helped facilitate the interview.

And finally, I want to correct two oversights from the last issue of MR. It was my intention to thank Hakim Bellamy for his help in all aspects of our publishing the segment on Amiri Baraka in that issue, which I failed to do. It could not have been done without his excellent assistance. And I want to clarify that one photo of Judson Crews which we used (p. 168, the poet in sunglasses and straw hat), though provided to us by Arden Tice, was taken by Diana Huntress. We greatly appreciate the usage of that photo, one of the best of Judson. Our apologies for these oversights. —Gary L. Brower

The Malpaís Review seeks to expand upon New Mexico’s rich and diverse cultural heritage by bringing together poetry, poetry translation, essays on aspects of poetry from writers around the state, the USA and beyond.

The Malpaís Review seeks to expand upon New Mexico’s rich and diverse cultural heritage by bringing together poetry, poetry translation, essays on aspects of poetry from writers around the state, the USA and beyond.

The issues will be published quarterly. Each issue will take 10 to 20 pages for one featured writer with the remaining pages open to everyone else. Some interior pages may be used for black and white artwork. Gary L. Brower, Editor

Subscriptions: $40 for one year (4 issues) postage paid. Single issues: $12 + $3.50 shipping. Make check payable to Gary Brower, Malpaís Review, POB 339, Placitas, NM 87043. The Malpaís Review is a 6×9 hardcopy publication between 120 and 150 pages each issue.

READING PERIODS:

Spring issue: Oct, Nov, Dec

Summer issue: Jan, Feb, Mar

Autumn issue: Apr, May, Jun

Winter issue: Jul, Aug, Sep

POEMS:

Malpaís Review seeks original poems, previously unpublished in North America, written in English. Any topic, but we despise hate inciting and pornographic work. Submit 1 to 5 poems, no limit on length, but once you hit 10 pages call the submission done (unless the submission is a single poem that is longer than 10 pages). Notification of acceptance will take place within 1 month of the closing of a reading period.

One submission per reading period. If your work is accepted into an issue, please let one issue go by before you submit again. In other words, we will publish your work a maximum of twice a year in an effort to keep the voices fresh. No simultaneous submissions.

ESSAY:

Essay topics: poetic criticism, history, theory, a specific poet or poem. Essays should be original and previously unpublished in North America. Length may be up to 5000 words.

TRANSLATIONS:

Translations, both poems & essays, will be considered. Required: permission of the original poet is required along with a copy of the poem in its original language (assumes poet is living and/or copyrights are still in force). We intend to publish both the original poem and the translation if space permits.

FEATURED POETS:

Will be invited by the editorial staff for each issue.

ARTWORK:

1-3 Digital images should be saved as JPG (JPEG), at a resolution of 300 dpi. (make sure you set your email to attach the “actual” image instead of allowing the email program to reduce the image size.) Set images to CYMK. If the image is selected for showing in the interior of the issue, it will be converted to greyscale. Remember that vertical images are easier for us to work with over horizontal images.

HOW / WHERE:

Electronic submissions preferred. Please send your poems in the body of an email. Due to the risk of viruses, we will discard, without reading, any poetry or essay submission emails with attachments. If your poems have unusual formatting, note it, and we will ask for an file attachment (such as a pdf, doc, rtf file), if the poem is accepted. In the subject line of the email, please place the words POETRY or ESSAY, a dash, then your name. Example: poetry – JQ Public.

poetry@malpaisreview.com

If you do not have access to email, please send hard copy to: Malpaís Review, POB 339, Placitas, NM 87043. Include an SAS Envelope or Postcard for response. Submissions without SAS Envelope or Postcard will be discarded without reading them. Submit ARTWORK in a separate email from poems or essays. Artwork may only be submitted via email.

If you do not have access to email, please send hard copy to: Malpaís Review, POB 339, Placitas, NM 87043. Include an SAS Envelope or Postcard for response. Submissions without SAS Envelope or Postcard will be discarded without reading them. Submit ARTWORK in a separate email from poems or essays. Artwork may only be submitted via email.

art@malpaisreview.com

Include a short, third-person biography with the submission.

RIGHTS:

Malpaís Review seeks first North American Rights of your work to appear in our hardcopy publication and reserves the right to use your work in a future “best of issue.” Rights revert to author upon publication.

Leave a Reply