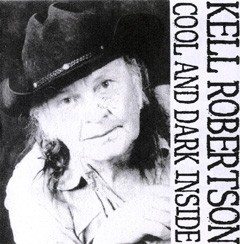

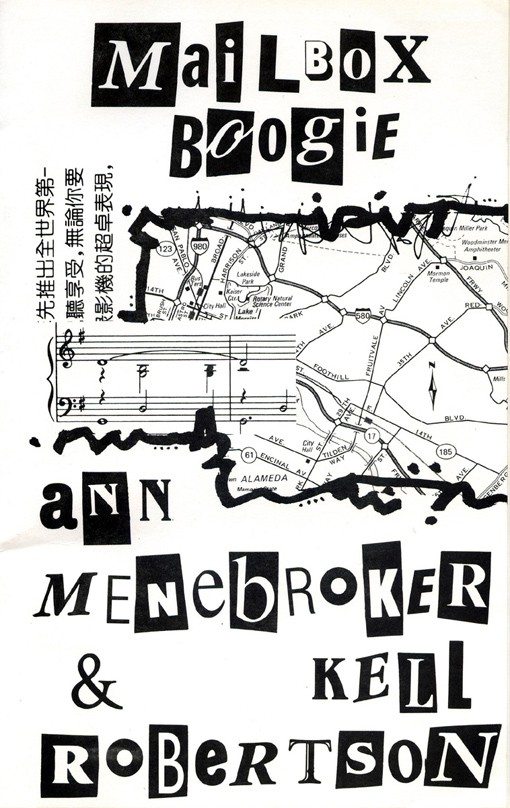

In his Introduction to BEAR CROSSING Kell Robertson teases out the role his life’s experiences have played in his writing. He says,

This little selection of poems was put together from the scraps of paper found in the bottom of my old tin suitcase. … I like this book because it somehow says in a very few words what I’ve been trying to say over a lot of years.

The language of poetry has a moral and aesthetic purpose that elevates this task of autobiographical writing, particularly if you’re persuaded by the smattering of American terms filtering through the poems — rattlesnake, tequila, frying corncakes, chittering squirrels, whiskey, country music, a Hopi, Indian songs / Cowboy songs and gumbo clay — terms that are more readily identified with the iconography of small town America than anywhere else.

Someone once said that you shouldn’t use poetry to tell a story, but Robertson chooses to ignore this. Robertson writes about people and places. It’s his forte. His poems convey a sense of landscape and human players: odd characters that he came across when he was working in a day work place called Labour Force in Ocala, Florida, and journeying throughout the U.S.

The characters peopling Robertson’s poems are tended with a sensitivity and humour involving not a little compassion. Tended with humility too — or maybe it’s just the wariness of someone who is an outsider. In the title poem, BEAR CROSSING, whilst he is

Flagging traffic for a road crew

he comes across a black bear and her cub:

The flagman at the other end said

he saw the bear too and, over a hot dog,

and a cold sodapop at noon told me

he wished he’d had his gun boy he’d

have shot the sonofabitch right in

the belly, her guts all over the

road.

Robertson leaves the impression of someone who is not quite at home with this scene, drawing back when he sees

the blood on my boot this morning

as thick as the sky up there.

In many of the poems Robertson seems to be identifying the people and places of the American heartland, so it’s not surprising to find him inherently curious about the desert in A FINE PLACE TO BE:

Popping open a hot beer at dawn

out on the desert, coughing up

and spitting remnants of

tobacco stained dreams,

very real granite gravel

grinding into my knees as I

fry stolen bacon in an iron skillet

over a fire made of dry

popping driftwood, my friend’s

gentle mare chomping, snorting

down the dry wash where

I tethered her.

But the poems are never hard-edged or bleak; the poems capturing nature red in tooth and claw, often wrapped with reverence and awe, a contrast to the offhand dismissal of those who live in and absorb these scenes on a daily basis. Clearly, however, his perceptions are not merely the awed appraisals of the outsider. Sentimentality is saved by the author’s clear eye and descriptive powers. In OLD MAN NEWBERRY he describes this odd character in detail:

Newberry barefooted

in tennis shoes with

holes in the toes

walks across the street

to the store for beer

clutching the exact change.

Newberry reels

in a drunken dance

to crush beercans

to supplement

his social security

in the back yard.

Robertson’s response to living and working in the American hinterland is to write of the issues that concentrate the minds of many of the people who live there. In OF BATS AND DRUNKS, for example, there’s no overblown rhetoric, simply a poet’s sensibility at work with his clear-eyed appraisal of the situation:

We sit around

our small fire

drink whiskey

and tell stories

making ourselves

into legendary figures.

Indigenous people are brought into the poems with an easy relationship, as we see in CORONADO NATIONAL MONUMENT:

My friend Jimmie

a Hopi

gathers his pennies

and buys us

Tokay

and we drink it

under the cut bank

of the Rio Grande

he throws the three

extra pennies

into the river

The mantle of the poet affords a freedom of expression and scope for integrity. It’s apparent with Robertson in poems such as LABOUR FORCE #1, where he describes his experience in the Labour Force:

We were not allowed to take off

our shirts and it was a quarter

of a mile down the road to take

a piss behind the big pile of mulch

in the glade. The owner came home

in the afternoon, got out of his Rolls

and glared at us as if we were

some kind of necessary insects

on his prize winning lawn.

There’s a tolerance in Robertson’s writing that is admirable and I respond to the general tenor of his approach. When it comes to judging others — whether it be a preacher’s son or a guitar player – Robertson is both generous and forbearing. He certainly doesn’t romanticise hardships and loneliness, but offers a fair hearing, which is about as much as one can ask for. His words demonstrate concern and a desire to come to terms with difference — both of character and place. Here we have his description of what Thunderlip Jones, the guitar player from the long poem THE SAGA OF THUNDERLIP JONES does on Saturday nights:

Saturday nights were fine to Thunderlip Jones

nobody called him worthless while they were laughing

& he went out into a world of Saturday nights

learned the loneliness of empty stages

skid row hotels, bars in the afternoon sun

after or before the crowd

empty feelings when the song is done

but he continued to sing

I suspect Robertson writes for himself, cataloguing the questions and answers that inhabit the boundaries of his experience.

It’s a kind of beat biography of my own absurd self,

he says of THE SAGA OF THUNDERLIP JONES.

A mix of myth and reality that I will probably never publish in its entirety.

NEW YEAR’S EVE is a simply written poem, simply told, with no more than two or four words to a line. It describes the poet’s journey across the desert to the nearest town:

After I eat

I will walk

back to town

and get drunk and ride

the high lonesome

again.

The next group of poems, THE MARR GIRLS, DEPOT CAFÉ, TAOS PLAZA AND SUE, describe some of the women that Robertson came across in his wanderings: the Marr girls

buck toothed but wonderful

in their bright flowersack dresses

the waitress who

never stopped talking

(never said much) but

never stopped talking

a young girl among the hollyhocks scratching an infection

on her plump thigh

and Sue, whose

husband makes faces

out of dried apples

which she sells

over the cash register

LITTLE HOPE CEMETERY describes the

ragged burial ground

where Molly S. Dunn’s grave is covered with

prophylactics

a pair of dirty yellow panties

and a half pint bottle of Jim Beam,

all empty

The collection ends with GREEN LANTERN BAR/EL PASO, TEXAS, where Robertson is seen writing in his notebook and the barmaid, Karen,

a gringa

from Kansas

looks over his shoulder:

“You don’t fool me,” she says, “We’re both hustlers.

I hustle for money and drugs —

you hustle for these words of yours.”

It seems a fitting end to Robertson’s often lonely journey where the lines of his poems and the notes of his songs are his only companions.

Robertson shuns the off-the-rack constraints of conventional verse to suit himself; perhaps — even to have fun. With him, there’s an itch, the background stuff he can’t discard, the simple normative experience of someone who thinks and records. An honest and insightful attempt to see into the hearts and minds of his fellows and a need to capture the essence of heartland America is what I take from BEAR CROSSING. by Patricia Prime.

Leave a Reply